It was clear as soon as we arrived in Puno that it was nothing like Arequipa. If Arequipa is the White City, then Puno is the Brown City. Its bleak look is reinforced by the universal use of corrugated iron roofs. Nothing says shanty-town like those wavy lines. But we weren't here for the city - we were here for the lake. Lake Titicaca is the highest navigable lake in the world, shared between Peru and Bolivia. Its most curious feature, at least for me, is the group of 42 islands floating half-an-hour off the the coast of Puno, called the Uros.

The name of these islands derives from the the name of the people who inhabit them. The Uros people lived happily alongside their other neighbours on the patch of land that is now the northern edges of Puno. Then the Inca came. The Uros felt the need to put some space between themselves and the spreading influence of the Inca, a reaction that can be readily understood. The only space they could find, however, was on the lake itself. At first they took to boats, then built little houses on those boats. In the case of both the boats and the houses, their primary construction material was the totora - a reed that is found growing in the waters all around the edges of the lake - right out as far as the current location of the islands themselves. In an excellent example of making the best of what you have, the Uros people used this reed for food as well. They took things further again - one might argue in a somewhat obsessive way - to devise a mechanism for constructing floating platforms from large blocks of roots of the totora. The Uros islands are a 600-year-old refugee camp.

Today, most Uros leave the islands at school age and don't come back. Why would they? There's no running water, precious little electricity (a few solar panels) and in any case, the Inca have been gone for quite some time. Those who remain on the islands live mostly by grace of the tourism they generate. Conservationism, this time of a unique human culture rather than an endangered species, owes much to the positive power of tourist dollars. There was no pretence in our encounters with the Uros. It was clear that they were used to boatloads of visitors, and they greeted us with song, dressed in colours that were sure to dazzle. They showed us, though the interpretations of the guide (they spoke neither Spanish nor English, but a pre-Incan dialect called Aymara) how they lived, what they ate, and with whom they traded. The experience was choreographed, neatly arranged for easy consumption. But there was no getting over the fact - we were on a floating island. We visited three of them in fact. It was home to these people. This was a way of life that was very real, totally unique and had been in place for 600 years or so.

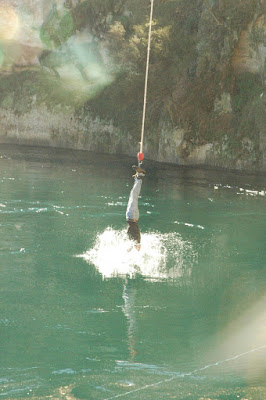

Nina and Sara loved it. The softness of the upper layers of reed underfoot was a delight. What could be cooler than a place where you could do the jackass as much as you want and fall flat on your back with impunity. Dry land seemed unreasonably hard and unforgiving after a few hours with the Uros.

Sara is usually the dressing-up kind, but this time it was Nina who volunteered to try out the Uros traditional dress.

The islands are a living museum, a tribute to innovation in the face of adversity, and a simple undiluted pleasure for visitors.

Our afternoon program took us south of Puno, along the shores of the lake to a small town called Chucuito. There are a lot of interesting corners to this otherwise quiet and neglected town. There is the church of Our Lady of the Assumption, from where the local platoon of the Inquisition maintained adherence to accepted orthodoxy on the part of the colonising Spanish, much like the Gestapo kept the National Socialist line in Wehrmacht outposts a few centuries later. It occured to me that I wouldn't have fared very well in Chucuito at that time. Not for my agnosticism in particular, but because of my perverse ideas on what constitutes humour: Sooner or later I would have thought it a jolly jape to ask the Grand Inquisitor exactly what it was that Our Lady was Assuming.

My daughters, who if they could would have built their own Uros islands a long time ago to take refuge from my 'jokes', were less impressed with this part of the days activities. Not even a field of stone penises could impress them. The Inca Uyo, sometimes known as the Temple of Fertility, is actually a solar observatory which was probably built to indicate the beginning of important moments in the agricultural calendar. The dozens of stone phalluses seem out of place (well, yeah!) and were perhaps taken from elsewhere and put into the Inca Uyo by well-meaning locals trying to reconstruct Inca heritage destroyed by the conquistadores. As such, they stand there in an act of defiance - one bunch of pricks against another.

But the idea of the Temple of Fertility stuck. Even today there are reports of women who visit the place in order to increase their chance of getting pregnant. The reports don't mention if they take their partners with them (which would seem like a sensible backup plan). Whatever erotic charge the temple might posess is undone by the belfry of the church of Santo Domingo, which peers in from across the road, silently outraged but too elderly to quite remember why.